Alcohol can't be that bad if it feeds us

An entire industry shattered

No booze. That was the directive from government following the strict Covid-19 coronavirus lockdown imposed on South Africa in March.

It was meant to free up the emergency rooms of hospitals that were frantically gearing up for an expected tsunami of Covid-19 cases. According to the government, this has worked.

Hospitals all over the country have experienced dramatic drops in trauma cases and the numbers of alcohol-related admissions have decreased. But it has had a downside. The revenue service has reported losing hundreds of millions of rands from the ban on alcohol.

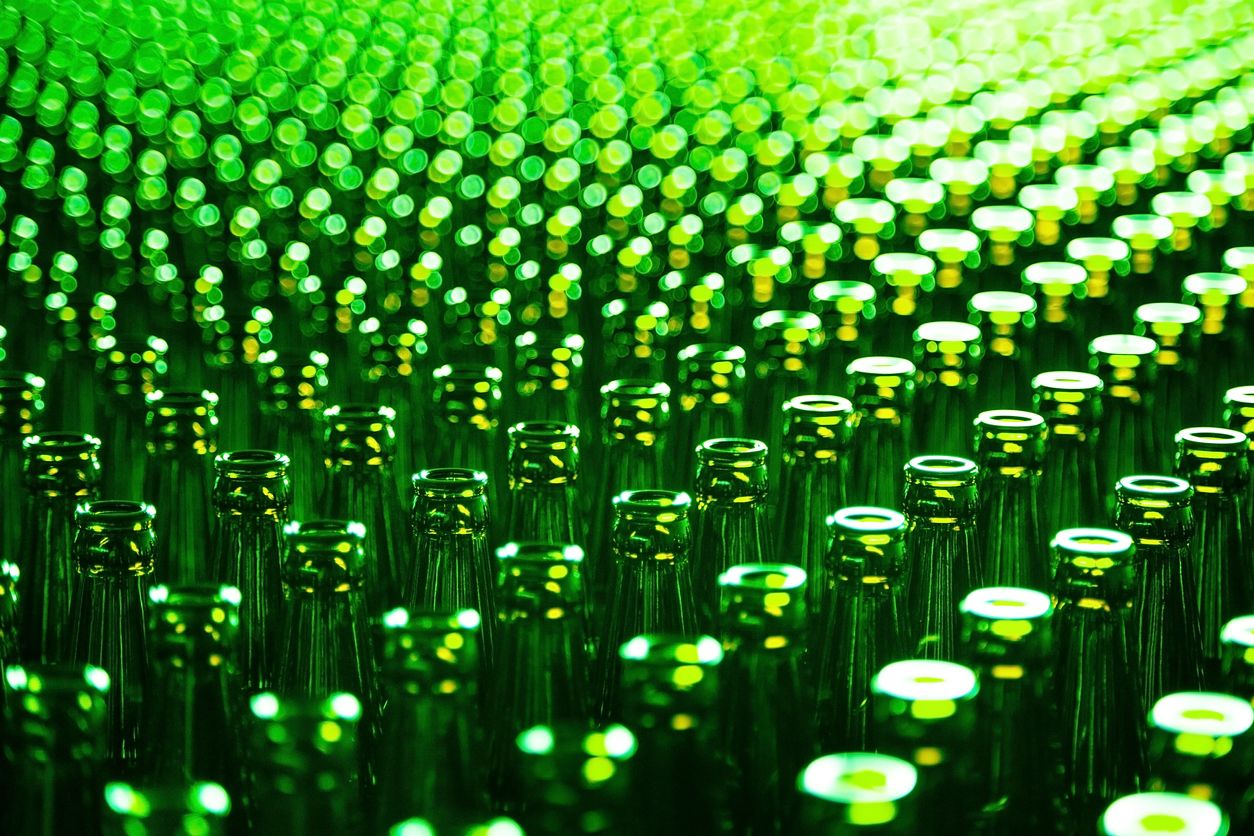

And both the alcohol and the glass industries, whose fortunes are intertwined, are taking major strain.

THE GLASS SECTOR

According to Mike Arnold, CEO of Consol Glass, “about 82% of sales of the glass container industry are to the alcoholic beverages sector”.

He told City Press: “The glass container industry contributes R11.83 billion in total to the national economy, which equates to 0.3% of South Africa’s gross domestic product. The glass container industry and related sectors employ about 26 300 people economy-wide (direct, indirect and induced).”

Arnold added that the effect of the lockdown and reduced sales for the glass packaging industry because of the extended ban on alcohol will be felt throughout the glass value chain.

“Under level 4, the glass container industry is able to return to 100% production under certain conditions,” he said.

“In reality, however, the majority of output from the industry is sold to the alcohol industry, which remains in lockdown under level 4 and will be highly restricted under level 3. Therefore, both level 4 and level 3 give the glass container industry little relief in terms of increasing output and/or sales to generate cash.”

Shakes Matiwaza, managing director of Isanti Glass, said: “Even under lockdown, our operating costs are very high as we have to keep the furnaces operating at a minimum of 50%. You can’t just switch a glass furnace on and off, so fixed costs such as energy and labour remain in place.

READ: Pressure mounts on government to lift ban on the sale of alcohol and tobacco

“The industry is spending more than R8 million a day just maintaining its assets, but with no sales, except for about 15% output that goes to the food industry. As a result, the financial reserves of the glass manufacturers are almost depleted. If we’re to recover, the ban on alcohol sales needs to be lifted as a matter of urgency.”

MONEY DOWN THE DRAIN

According to director of regulatory and public policy at South African Breweries (SAB), Hellen Ndlovu, “SAB produces 10 million litres of beer a day, 50 million a week and 250 million litres a month”.

“So far 1.7 million litres of beer have been disposed of (by 14 May 2020),”she told City Press.

“This is done at a rate of between 200,000 and 300,000 litres of beer a day over the past week. The longer SAB is not allowed to trade, the higher the number of beer to be dumped.”

Ndlovu said she was concerned by the impact the ban on alcohol was having on the economy, more so since “SAB’s value chain is wide-reaching”.

“Our entire supply chain has been affected by the alcohol ban,” she said.

BEER IN NUMBERS

250 million - The litres produced a month.

1.7 million - The litres that have been dumped

“Our supply chain incorporates a total of 3,739 suppliers of which 1 345 are small and medium businesses, supporting in excess of 140 000 jobs. In addition, our business sources agricultural inputs from more than 1 277 farmers of which 757 are emerging farmers. The longer we are unable to operate, the bigger the ripple effect.”

She added: “Revenue Service commissioner Edward Kieswetter alluded to the significant losses made to SARS as a result of this total ban on alcohol, which we estimate the immediate loss to the government in excise tax would be R500 million, as the state does not collect excise for unpacked beer.”

“This would literally be pouring that tax revenue down the drain, at a time when government – and the citizens of South Africa – have an urgent need for those funds.”

“To put the revenue loss in perspective: A loss of R285 billion in revenues would be larger than the R229.7 billion budget allocated for SA's health sector for 2020.”

Isanti Glass managing director Shakes Matiwaza said waste pickers like Samuel Makgetha and Daniel Mosia would be hard hit by the alcohol restrictions imposed during the nationwide lockdown.

He told City Press: “The lockdown has had a severe impact on the informal recycling industry as up to 90% of revenue has been lost by these guys up to this point, according to the FTI Consulting research. In turn, the economic well-being of the communities sustained by these collectors is at risk.”

“The alcohol industry contributes approximately 82 – 85 % to the glass industry revenues. It is the backbone of the glass container industry business. Without alcohol, the glass container industry in South Africa is not viable,” he said.

But the knock-on effects of the booze ban have affected those who live on the fringes of society the most.

South Africa’s thousands of recyclers are feeling the effects more than anyone else.

“I go through people’s bins as a way of making money to survive,” says Samuel Makgetha, who has been recycling as a source of income since 2007.

“The lockdown has definitely had a huge and negative effect not just on the items I now find in bins, but also on how much I find.”

Some have given up. Tokelo Kampong has stopped going to work.

“I know I won’t find a lot of what I want to collect. Items have reduced drastically since the lockdown. Even at the scrapyard, where I sell what I’ve collected, the amount they give me per kilogram has gone down. I’m guessing they, too, have felt the effects of the lockdown.”

As another recycler, Daniel Mosia, said: “No alcohol doesn’t just mean no alcohol – it also means no empty bottles, which in turn means less money for some of us. So alcohol can’t be all bad.”

The alcohol ban has not only dampened spirits, but has also had adverse effects on those whose livelihoods depend on the bottles. City Press journalist Palesa Dlamini followed some of Johannesburg's recyclers and heard their stories. Video: Palesa Dlamini/City Press

The alcohol ban has not only dampened spirits, but has also had adverse effects on those whose livelihoods depend on the bottles. City Press journalist Palesa Dlamini followed some of Johannesburg's recyclers and heard their stories. Video: Palesa Dlamini/City Press

Goiing through bins to survive

Samuel Makgetha

Waste picker Samuel Makgetha (38) is struggling through the 5am chill. He prepares his trolley, which he calls his “carrier ride”, before embarking on the more than 10km walk from Doornfontein to Westbury, eastern Johannesburg.

“It’s time to go work,” he says softly, as he fixes his face mask with one hand.

Huddled against the cold with his gloves, a beanie and the now-required face mask on, Makgetha trundles down Davies Street. His trolley’s rattle follows him with every step he takes.

On this morning, like every other, Makgetha must get to his destination before “the Pikitup trucks and other waste collectors get to where I’m going”.

To achieve this, he must walk through four areas – Newtown, Braamfontein, Brixton and Auckland Park.

READ: Pressure mounts on government to lift ban on the sale of alcohol and tobacco

As he makes his way through the dark streets, alternating between walking and riding his trolley, he makes sure that he avoids oncoming traffic. His counterparts aren’t far behind him, riding down the road too.

Arriving at his planned destination – Westbury – an hour later, Makgetha says he’s happy that the sun’s out so that he can work effectively.

He clearly knows where he’s going as he walks up to two Pikitup bins that have been placed outside a home in Wessler Street.

“I’ve been doing this since 2007, when I came to South Africa from Lesotho. A friend from back home introduced me to it. I go through people’s bins as a way of making money to survive,” he says as he sets up his trolley, ready to fill it.

“I GO THROUGH PEOPLE’S BINS AS A WAY OF MAKING MONEY TO SURVIVE ”

~ Samuel Makgetha

As he opens the first bin, the father of one explains: “I’m looking for cardboard, plastic containers and bottles, mostly,” he says as he ruffles through the contents. They’re almost swallowing his head, which is dipped inside the bin.

“I no longer find beer bottles, which I could sell at the scrapyard or at bottle stores, where I could make more money. I could sell a single beer bottle for anything between 50c and R1.50. Lately, I can’t find even a single one, whereas before I could collect up to more than 50 at a time. So this has meant less money.”

Extracting an empty bottle of vodka from the dustbin, he tosses it aside and says: “You see, these bottles I don’t collect because I know I won’t find enough of them to fill my sack. If it was a beer bottle and bottle stores were operating, I know I’d at least get R1 or R1.50 for it.”

He goes to different areas on different days of the week.

“Today I’m here in Westbury, yesterday I was in Westdene and tomorrow I’ll be in Hillbrow,” he says.

Although the number of dustbins that have been brought out is increasing, Makgetha works at a consistent pace. “I want to make sure I don’t miss important things I might be able to sell.

“The amount of money I get from the scrapyards depends on how much each sack I bring in weighs and what items are in them,” he says as he tosses plastic cold drink bottles into the sack that is secured on his trolley.

“I could get anything between 50c and R2 per kilogram at the scrapyard. It differs. I could get up to R500, which is the most I’ve ever got in a week.”

Makgetha, whose livelihood requires the “ability and willingness to walk tirelessly”, says he’s become accustomed to the working hours he’s endured over the years.

“Depending on which area I’m going to, I leave my place anytime between 1am and 5am,” he says. “Today I left at 5am and tomorrow I must be in Hillbrow by at least 1.30am.”

He’s suddenly joined by two women who greet him as they, too, begin to peruse the contents of the dustbins that surround him.

The three exchange pleasantries and the women move on to the next street, where residents have lined up their dustbins ready to be emptied.

One of the women – Nokuthula Phuza – finds a pair of broken shoes in a bin and slowly places them in a paper bag.

“I deal with clothes because that’s what my children and I need. I’m unemployed and this is how I try to somehow provide for them. What I hope to find on a daily basis is food and clothing that have been thrown out,” she says.

After working for about five hours, Makgetha heads home.

As he slowly pulls his trolley, now laden with his collections of the day, he says he’s disappointed by how little he managed to find.

“The Pikitup trucks arrived earlier than usual today, so I wasn’t able to go through all the bins I wanted to. So I’m heading back home. It wasn’t a good day,” he says.

Waste picker Samuel Makgetha (38) pulls his“carrier ride” during his 10km walk from Doornfontein to Westbury, eastern Johannesburg. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Waste picker Samuel Makgetha (38) pulls his“carrier ride” during his 10km walk from Doornfontein to Westbury, eastern Johannesburg. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Samuel Makgetha struggles through the 5am chill. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Samuel Makgetha struggles through the 5am chill. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Nokuthula Phuza goes through bins in the hope of finding clothes or food for her and her children. Today she finds a pair of broken shoes in a bin and slowly places them in a paper bag. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Nokuthula Phuza goes through bins in the hope of finding clothes or food for her and her children. Today she finds a pair of broken shoes in a bin and slowly places them in a paper bag. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Waste-pickers scavenges waste dumped by a garbage truck at the Marie Louise Landfill on Dobsonville Road in Roodepoort, Johannesburg. The Covid-19 outbreak in the country has made it difficult for waste pickers to put food on their tables. Picture: City Press/ Rosetta Msimango

Waste-pickers scavenges waste dumped by a garbage truck at the Marie Louise Landfill on Dobsonville Road in Roodepoort, Johannesburg. The Covid-19 outbreak in the country has made it difficult for waste pickers to put food on their tables. Picture: City Press/ Rosetta Msimango

Those who still manage to send money home

DANIEL MOSIA

In Westdene, a suburb a stone’s throw away from Westbury, 36-year-old Daniel Mosia has been hard at work since 5am, after having left home in Doornfontein at 4am.

It’s now just after 8am and he says he must work as quickly as he can “before the Pikitup trucks arrive”.

“I mainly collect plastic bottles like those of cold drinks, milk, cleaning things like Domestos and such. I also collect cardboard boxes and iron,” he says as he works frantically.

“I collect beer bottles, but they’ve been scarce because people can’t buy alcohol. I have to manage with what I can find. The money I got from beer bottles would be separated from money I made from cardboard boxes because I’d sell the 750ml ones back to bottle stores for as much as R1.50. That’s where the bulk of my money came from.”

The ban on alcohol has severely affected not just manufacturers, retailers and consumers, but the country’s most impoverished, who eke out what they can to survive in this way. No bottles means the difference between a meal in the evening or the prospect of going to bed cold and hungry.

Mosia’s wife and child are back home in Lesotho. He says he tries to send them money every month.

“I left Lesotho with the hope of getting a job as a contractor in South Africa. But when I arrived, things didn’t go my way and a friend from back home introduced me to this. I’ve been doing this for 20 years. I send about R700 a month back home and, with whatever’s left over, I survive as best I can.”

“I must make sure I return with a sack filled to the brim.”

He says he can’t let the approaching winter deter him: “I must make sure I return with a sack filled to the brim.” But as we leave him, his sack is still only a quarter full. It’s going to be another desperate morning for Mosia.

Daniel Mosia separates recyclable waste in rubbish bins in Westbury, Johannesburg. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Daniel Mosia separates recyclable waste in rubbish bins in Westbury, Johannesburg. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

He left his home at 4am. Although the sun is out it's still a bit chilly as Daniel Mosia goes through bins in the hope of filling his sack with recycling that he can sell for cash. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

He left his home at 4am. Although the sun is out it's still a bit chilly as Daniel Mosia goes through bins in the hope of filling his sack with recycling that he can sell for cash. Picture: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

Those who have given up

Tokelo Kampong

On the other side of the city, in Newtown, Tokelo Kampong sits at the gate of Bekezela, a place he calls home and where waste pickers like himself store their trolleys.

Bekezela doubles up as a hostel, where some people live, and a storage facility for the trolleys and the recycling they’ve collected.

While many of his counterparts return to store their day’s collectables, the 26-year-old says he decided not to go to work today.

The effects of the lockdown have left Kampong with little to look forward to.

“I know I won’t find a lot of what I want to collect. Items have reduced drastically since the lockdown. Even at the scrapyard, where I sell what I’ve collected, the amount they give me per kilogram has gone down. I’m guessing they, too, have felt the effects of the lockdown,” he says as he takes a puff of his almost-dead cigarette.

“We were unable to work for over a month and other people out there were also unable to work, let alone drink, which has now affected what we can find. The same goes for the money we get from selling what we have. It’s much less.

“On good days [before the lockdown], I could get about R2 a kilogram, but since we’ve been able to work following the announcement of level 4, I get about 50c per kilogram. It isn’t encouraging, especially after spending more than 16 hours on the street,” he says.

“Prior to lockdown, I could make as much as R800 per week, but since I’ve been working again, the most I’ve been able to make from selling is R300 in a week.”

Bekezela doubles up as a hostel, where some people live, and a storage facility for the trolleys and the recycling they’ve collected. Picture: Palesa Dlamini/City Press

Bekezela doubles up as a hostel, where some people live, and a storage facility for the trolleys and the recycling they’ve collected. Picture: Palesa Dlamini/City Press

Tokelo Kampong decided to not go to work today. The lockdown has affected every aspect of his livelihood, from the amount that he collects to the money he gets for it. Picture: Palesa Dlamini/City Press

Tokelo Kampong decided to not go to work today. The lockdown has affected every aspect of his livelihood, from the amount that he collects to the money he gets for it. Picture: Palesa Dlamini/City Press