WAS THIS THE SOUTH Africa they envisioned?

Remembering Rivonia

Nelson Mandela and fellow imprisoned Rivonia trial convicts, including Ahmed Kathrada who can be seen to the right of Mandela, revisit the lime quarry where the Robben Island prisoners worked. (Photo by © Louise Gubb/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

Nelson Mandela and fellow imprisoned Rivonia trial convicts, including Ahmed Kathrada who can be seen to the right of Mandela, revisit the lime quarry where the Robben Island prisoners worked. (Photo by © Louise Gubb/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

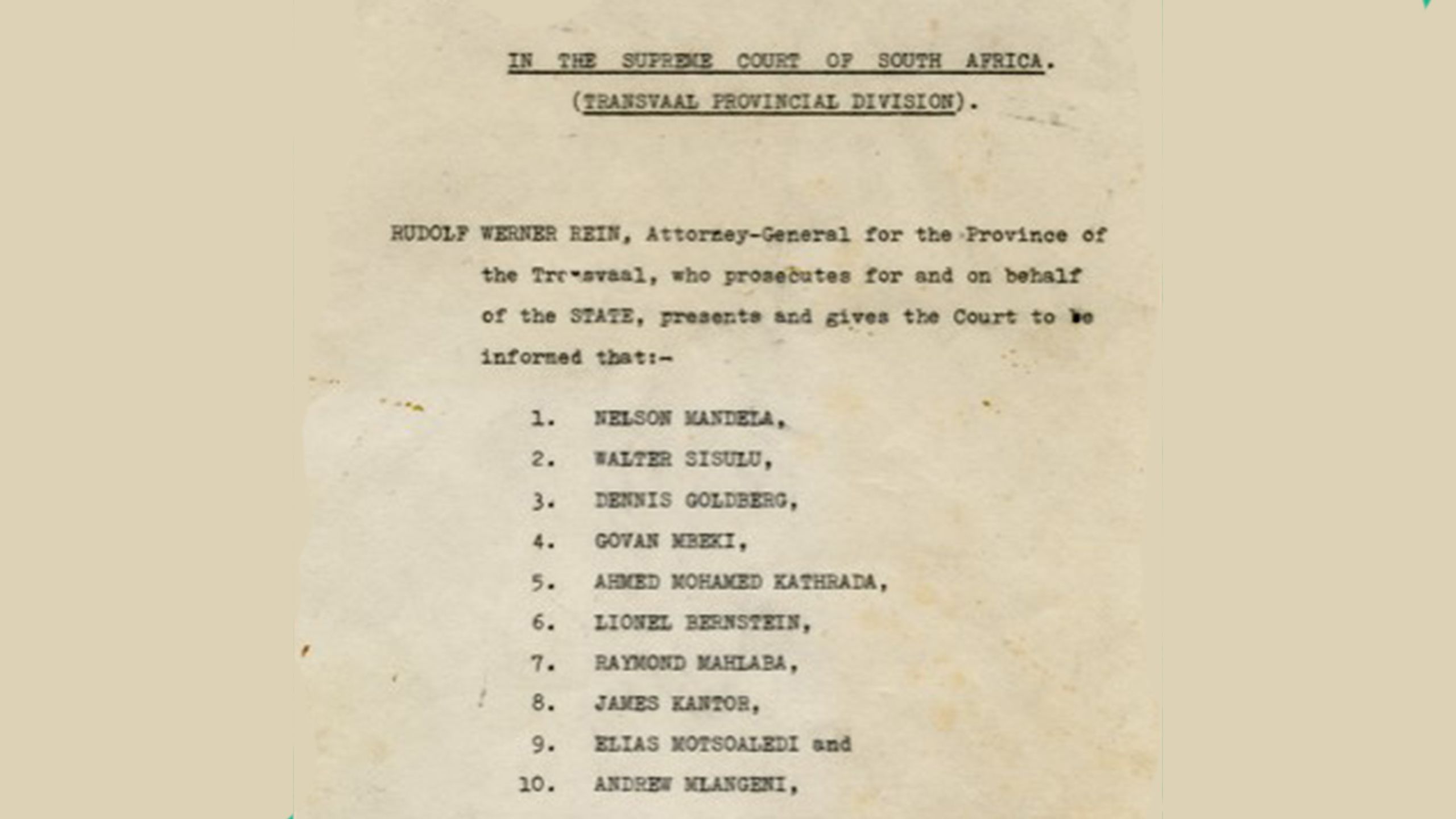

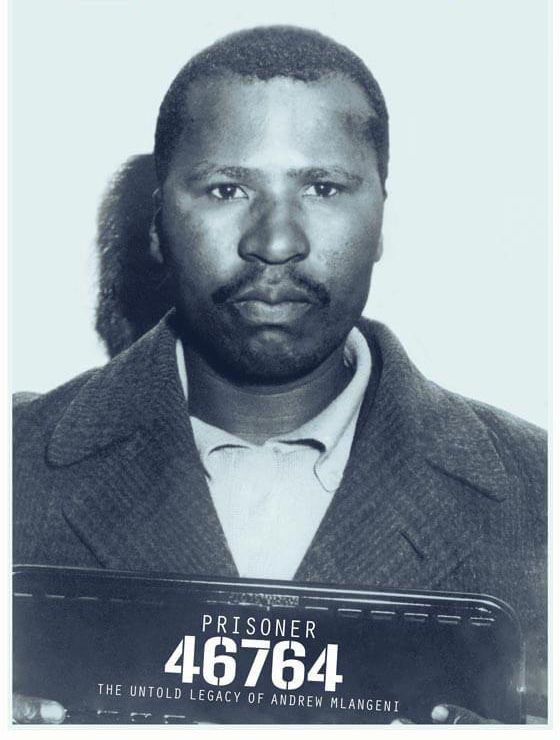

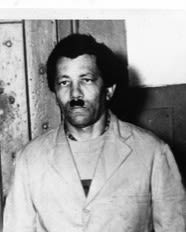

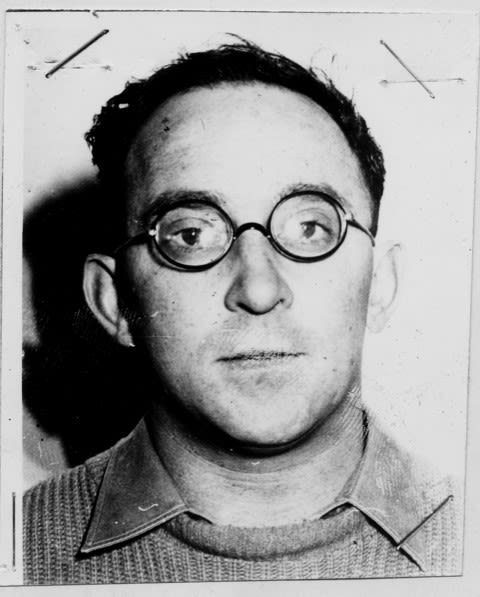

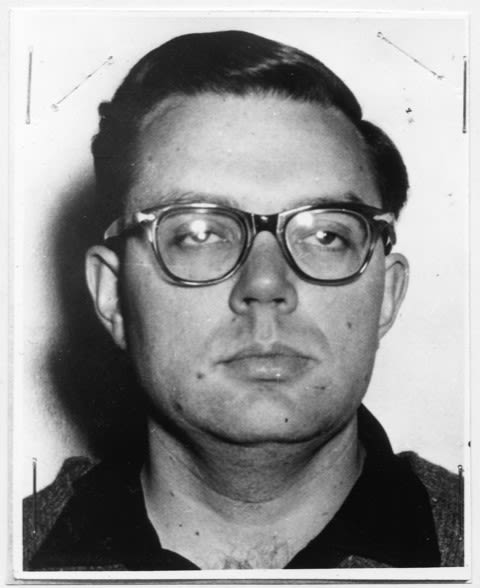

October 15 was the day on which most of the Rivonia treason trialists were released from jail.

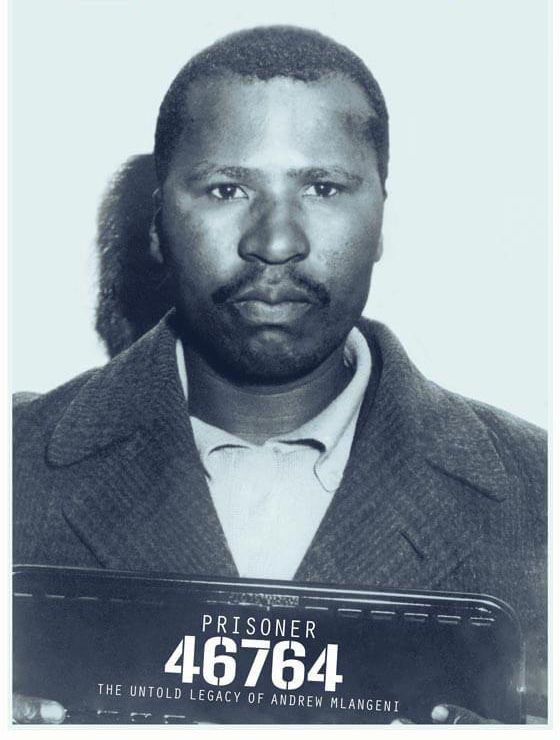

Those who were released 31 years ago included Walter Sisulu, Andrew Mlangeni, Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba, Elias Motsoaledi, Wilton Mkwayi and Jafta Masemola.

They had served sentences ranging from 25 to 27 years after they were originally sentenced to life.

City Press visited Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia where ANC leaders found holding a meeting in the Thatched Room were arrested, following a raid by security police in July 1963. The farm served as the ANC’s underground headquarters after the party was banned by the apartheid government in 1960.

City Press visited Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia where ANC leaders found holding a meeting in the Thatched Room were arrested, following a raid by security police in July 1963. The farm served as the ANC’s underground headquarters after the party was banned by the apartheid government in 1960.

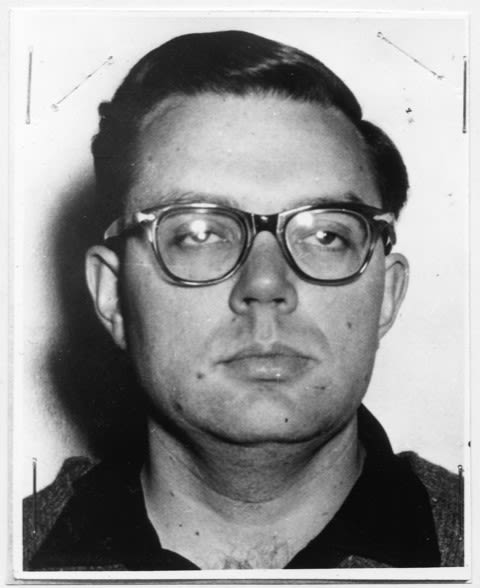

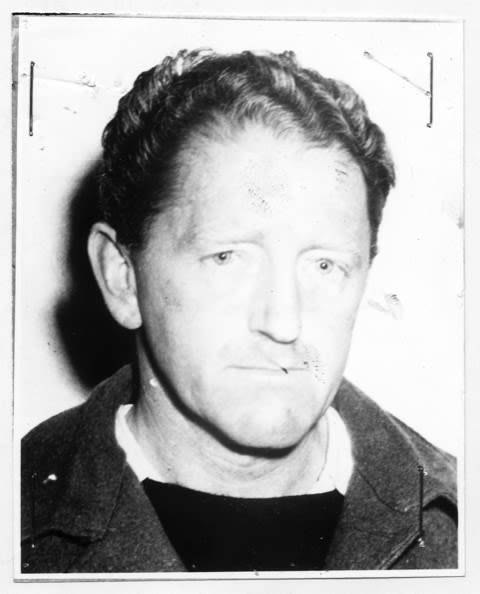

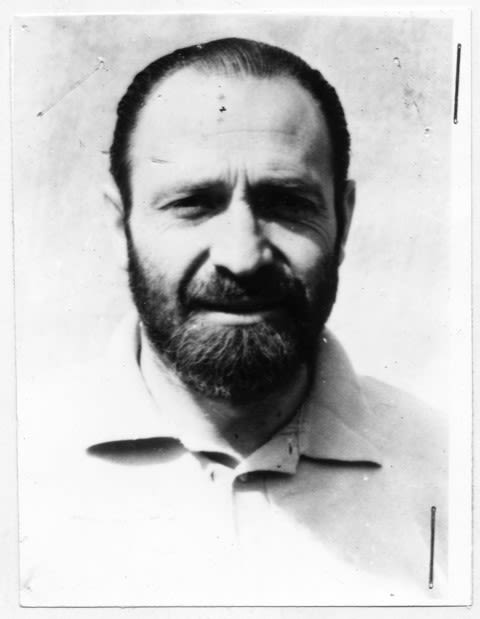

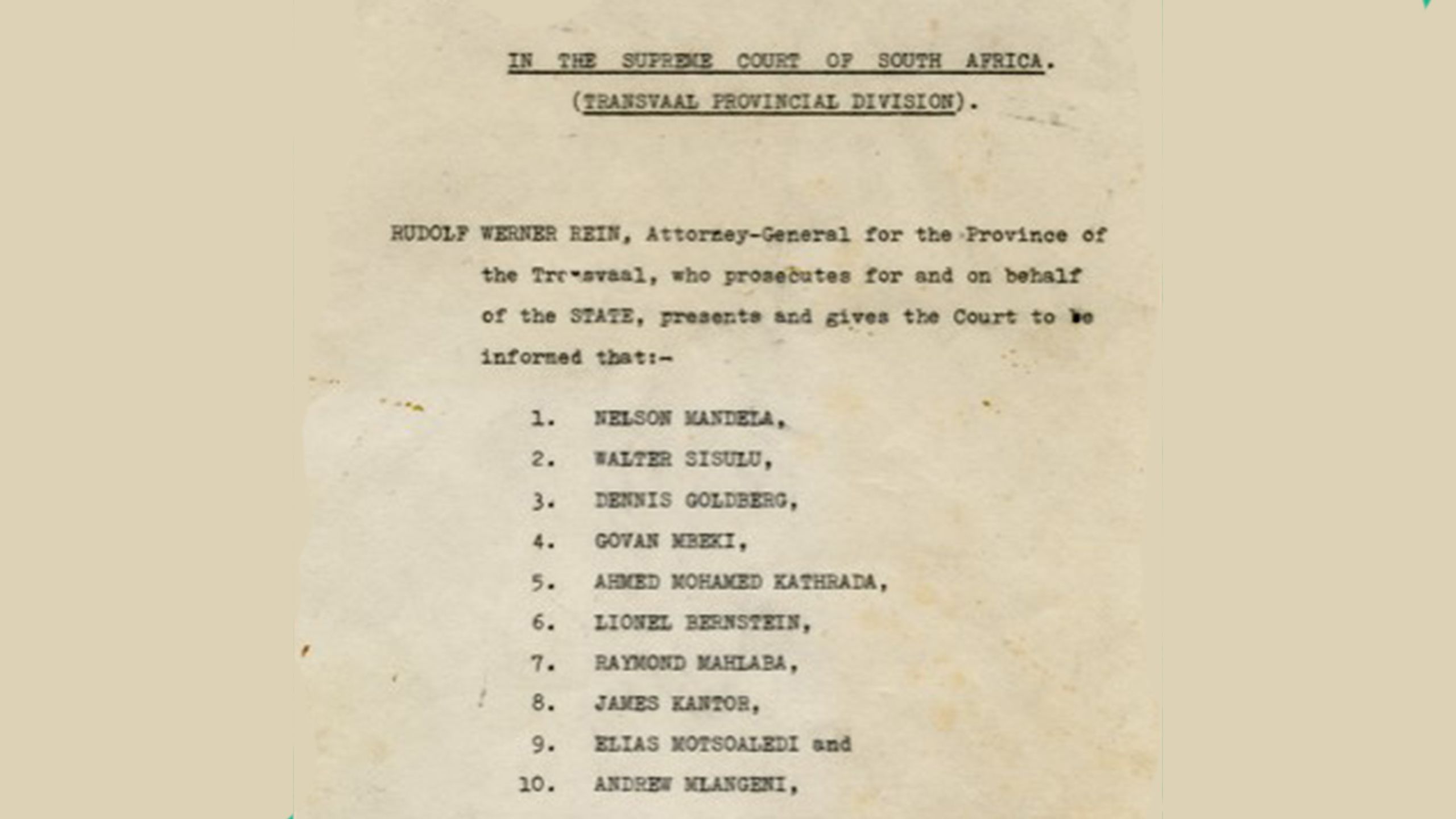

James Kantor, the unsuspecting eighth co-accused at the Rivonia Trial, while on trial asked his fellow accused to write mini biographies, which he included in his book A Healthy Grave, which was a recollection and reflection of his arrest and standing trial for sabotage.

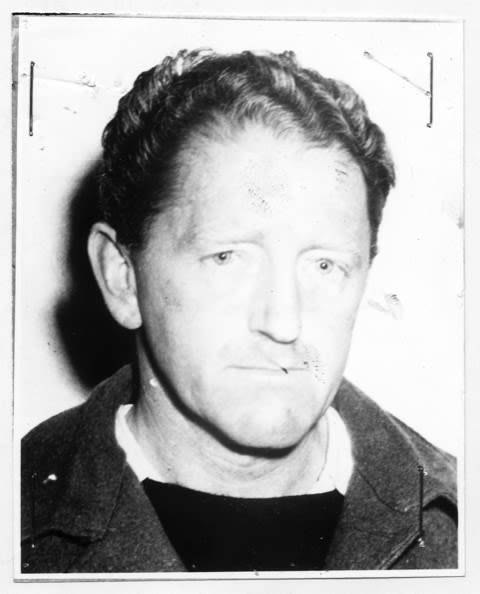

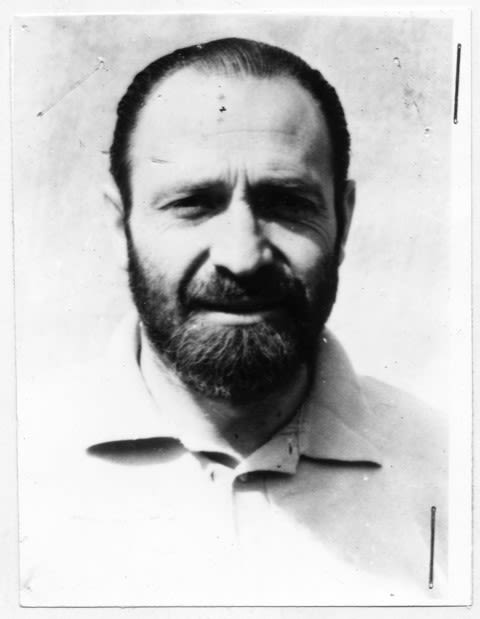

These are images of the original handwritten biographies written by the Rivonia Trialists.

City Press journalists Juniour Khumalo, Queenin Masuabi, Mandisa Nyathi and Setumo Stone, spoke to struggle activists, including those who were in exile and in the country, about what the day meant for them and many also speak of their whereabouts during that time.

Lindiwe Zulu

II was in Uganda when they announced that the trialists would be released, as I was still working at the ANC offices there. I was still in exile. While we were excited, it was quite scary because we did not know what to expect, we did not know what the future would look like.

Being a soldier, you do not think the enemy will just throw away their arms. We did not know the intention of the enemy. We were worried because we did not want to be swallowed by a system which would not allow us to be free.

Now we no longer have apartheid, we are living freely.

The current state of affairs is good because we are now living in a democratic state, but the only issue is that we are not yet economically free. We have issues regarding hunger, poverty, unemployment and land ownership.

The road towards a democratic state still needs to be worked on and it is going to be a journey.

Peter-Paul Ngwenya

I think about them (the Rivonia Trialists) all the time, almost every day. I always discuss their contributions with those who care to listen. The topic always comes up, especially when we look at the way things are now going in the country. I always think they – the majority of whom have passed on – are turning in their graves as they look down at what is happening to the democracy they sacrificed so much for.

Most of the trialists, while always hopeful that apartheid would be defeated, remained unsure or fearful about whether it would happen in their lifetime. As a result, they sacrificed so much and expected nothing in return. All they always aspired to was to replicate the selfless attributes and the desire for equality they possessed in the next generation. They had no exceptions other than to see our people freed from the shackles placed on them by the apartheid government.

I know for a fact that Nelson Mandela did not want to be the first president of a democratic South Africa. He always held the belief that a younger more energetic individual should have taken that position but, as a symbolic gesture, he accepted that role. I was of the belief that he wasn’t even going to finish that first term; I was expecting a scenario in which he handed the reins over to his deputy and that was honestly the case.

I am on my way to see Tokyo Sexwale and I am sure we are going to discuss the calibre of individuals in these trials and the huge gap that has been left by their passing.

One person I got to know fairly well and who became my personal mentor while we were on Robben Island was Govan Mbeki.

While we were in prison, depending on which political affiliation we came from, we all had our own political syllabus. I got to Robben Island in August and most new inmates had been taken through the syllabus so I had to catch up. Mbeki then became my personal tutor and assisted me through what other inmates affiliated to the ANC had already been taken through. Mbeki basically taught me everything I know about the ANC.

Besides that, I also learnt from him the need to be patient and never to enter into a debate on a topic that I was not well versed in.

Another thing that I will remember fondly about Mbeki is that he gifted me with a book, The Last White Parliament by Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, while we were still on Robben Island. He asked me, “What do you think of this text?” I told him, this is one white man who should have been born black. He taught me a lesson, even at the height of oppression, he said, this should teach you that not all white people are racist. Since then, I have learnt to give everyone the benefit of the doubt. People have to prove to be are racist; I don’t just label them based on how they look.

He also taught me the importance of education, something that is no longer prioritised. I studied and attained a BCom honours degree while I was in prison.

I always look at our political figureheads, in particular ANC leaders when they are attending events – they are always dressed in T-shirts. Back then, our leaders were always sharply dressed in suits; it told you that they meant business, they were people who took the citizens and the work they were doing seriously.

Sadly, I am still here to witness the destruction of our hard-won democracy and have seen how some of these leaders were sidelined even when they were still alive. For you to be listened to by the ANC, you have to either still be holding a position of influence or, for the newcomers, buy a branch or a few branches; that’s the only time you will get any recognition.

I will tell you something, while the Rivonia Trialists believed entirely in the country’s democracy, there was a time when they interfered in democratic processes, in the sense that they would give counsel as to who should fill which position of authority and who shouldn’t. Because of their wisdom, their counsel was always listened to and their decisions always proved to be correct but, since that stopped, we are faced with our current dysfunctional democracy.

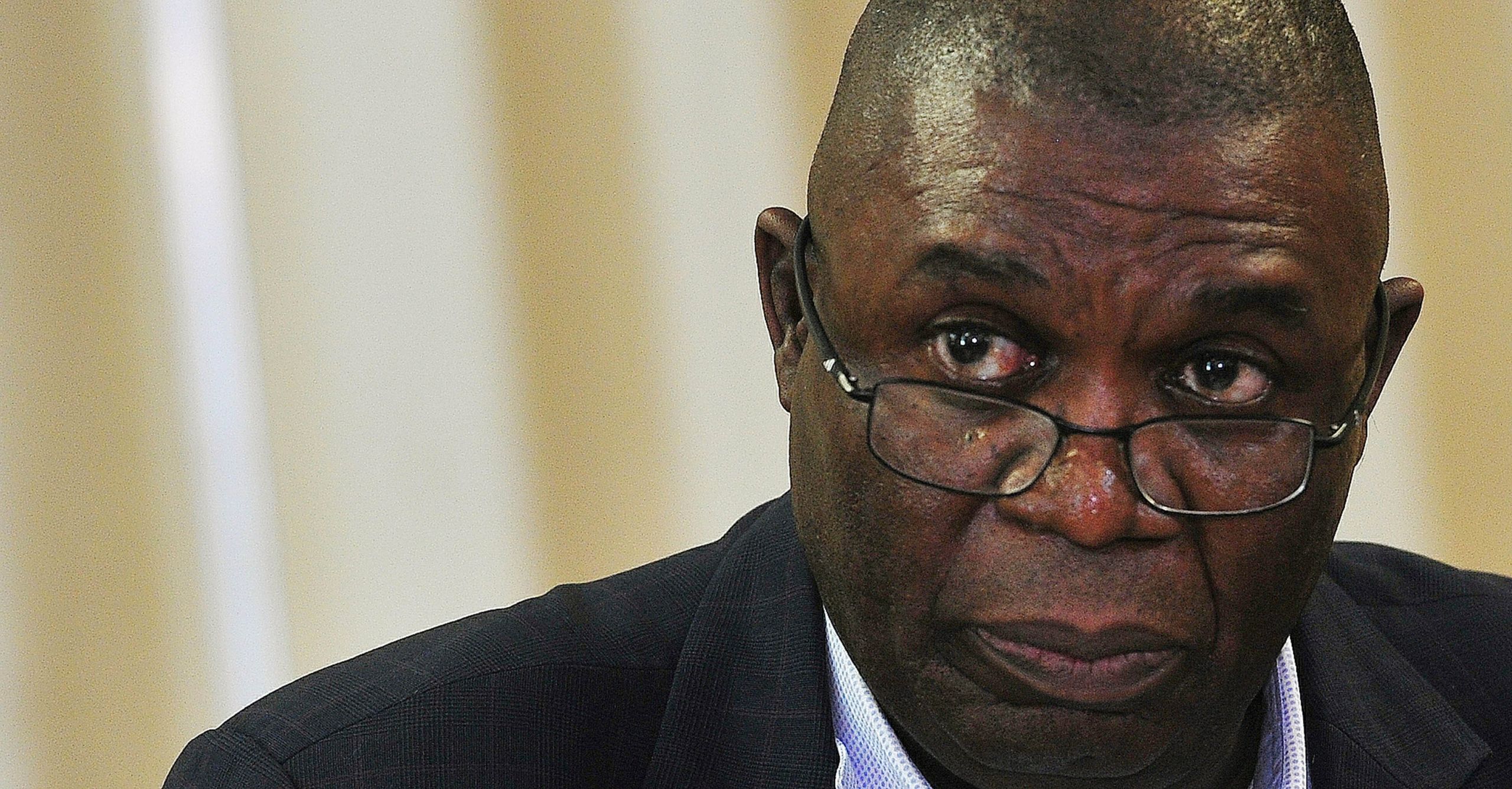

Sydney Mufamadi

When they were sentenced in 1964, I was only five years old, but that moment still had a telling impact on my life and directed my footsteps towards being so politically conscious. The first trialist I ever met was Govan Mbeki, who was released two years before the other prisoners – remember they were released in instalments.

Then later I was part of the delegation that went to visit Mandela in Victor Verster Prison where he was incarcerated. All of them served as an inspiration to millions of South Africans who were living under oppression. They were an inspiration to successive liberation fighters who followed in their footsteps.

When it drew closer to their release, a lot of South Africans took for granted that they would be released, without knowing the struggle that went into those negotiations. Freedom did not come as a gift.

For us though, who were part of the negotiations, we were obviously not surprised on their release, as we had been privy to the discussions. In political terms, we were ready for their release.

The apartheid government had been forced into a corner where they had to show us a gesture of their willingness to engage with us through releasing our leaders. We told them that we couldn’t talk with them without our leaders being the ones at the forefront of the negotiations. That was the condition attached to any form of engagement.

When Mhlaba was lying on his death bed in Port Elizabeth before he passed on, I went to visit him and he said words that have stuck with me all these years.

He said: “Why are you people (the younger ANC leadership that had taken over) doing this (engaging in corrupt activities). Why didn’t you at least wait until we were dead before engaging is such acts?”

I had no answer; all I knew was that he would leave this world a broken man because of the crumbling of our democracy that was unfolding before his eyes.

I wished that he had not said this only to me but to a lot more within the ANC. I have kept these words to myself but have decided to share this with not only South Africans but the rest of humanity.

The task of building a democracy does not have an expiration date. It’s an ongoing endeavour. We were freed because they [the Rivonia Trialists] did not disown the course of attaining freedom; as such, those of us who have been handed the baton should also not forgo the pursuit of freedom.

Mo Shaik

At the time of the release of the Rivonia Trialists, former ANC intelligence operative Mo Shaik was involved with the party’s Operation Vula, which was a high-level, confidential underground mission intended to infiltrate senior members of the party into the country in order to coordinate operations. In July 1990 the mission was busted and he had to go into hiding.

Shaik tells City Press that, in the period since the release of the Rivonia Trialists “South Africa went from an impending civil war to the transition to a democracy; then we had what was called the honeymoon period; then we had to grapple with the difficulty of governance; then we had the ten wasted years of bad administration; and now we are dealing with a crisis of renewal for the recovery that is essential to construct a better life from the ashes of Covid-19”.

“So, it’s amazing that in these past 30 years we have gone through a full spectrum of enormous hope and despair, hard work and failing institutions, and now we are back into despair and hope again.”

He says that, with the release of the Rivonia prisoners, the country was “slowly edging towards the point of irreversibility where South Africans were coming together”.

“Those were the early times when negotiations were in front of us. So there was hope that we could end the civil war that was gripping our country. It was a period of enormous hope.”

To date we have done many things right, says Shaik. But, he warns, the glue for the past 30 years, which kept us together as a country, is very fragile and it is breaking in a few places. The social compact that kept South Africa together for three decades is under severe stress.

“Perhaps now what we need is to put fresh glue back in. We have to find out today what it is that we have in common, and hold on very tightly to that. Of course, we have our democracy and Constitution and remarkable ability to talk about our problems rather than fight about them.”

He says we should have urgency in constructing the national dialogue so that we can come together again, in whatever form – political parties or civil society – to be able to ask whether we can construct a better future for the next 30 years.

“My fear is that there is fatigue. Compounded by a sense of hopelessness. The sense of hopelessness is leading to a withdrawal and detachment from all of us from the very same processes that we need to come together in, to be able to construct a better future,” Shaik says.

Ayanda Dlodlo

State Security Minister Ayanda Dlodlo, who was then in exile cutting her teeth in the ANC’s intelligence structures and the armed wing, Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), says “the anniversary is a pleasing reminder that the revolution was never in vain”.

“That proud moment when the Rivonia Trialists were released was a culmination of decades of a struggle for liberation that eventually yielded a vibrant democracy that has as its cornerstone the principles of justice, freedom and equality for all.”

She says that, in many ways, the year 2020 marks an end to an era. Earlier this year we bid farewell to two brave architects of the armed struggle, the last remaining Rivonia Trialists, Denis Goldberg and Mlangeni.

“As we reflect on the release of the majority of the trialists on 15 October 1989, we are engulfed with a sense of hope. Having overcome our dark past, we have a lingering belief that the challenges we face are surmountable and that we will one day realise the true aspirations of our nation as enshrined in our Constitution.”

She says news of the releases of their heroes sparked a jubilant moment, but one that was also quite cathartic. The emotional release after years of being in the underground structures in exile under the toughest conditions was overwhelming, she explains, adding that “it had taken sustained mental and physical resilience to survive and that moment was the much-anticipated sounding shot that we had indeed won the battle for liberation”.

Dlodlo says the current situation in our country is vastly different compared with then. “There is more inclusivity and diversity in our political, economic, social and cultural spaces now than ever before, though we have fallen short on some transformation quotas.”

Needless to say, more still needs to be done. We need to increase the participation of women in politics, decrease the racial and gender pay disparities across the economy, increase black ownership of companies, and eliminate all manifestations of racism and sexism across the different spheres of society.

She says the freedom we enjoy today has been hard-won. We still have battle-torn ex-combatants with deep emotional and psychological scars.

To this day, some have no roof over their heads, some are unemployed and struggling to keep their heads above water.

“I mention this because it is important to avoid the trap of complacency without acknowledging the difficult past. In as much as constructive criticisms are made on the state of our nation, there seems to be an ever-growing complacency without action, particularly over social media,” she says.

She emphasises that the importance of working together as a nation can never be overstated. “To win the challenges our generation faces, there needs to be a collective effort to overcome. Government alone can never win the battle against corruption, poverty, unemployment and gender-based violence, among others issues. We need an active citizenship that holds those in positions of power to account and that also proactively plays its part.”

Zakes Tolo

ANC veterans league leader in the North West, Zakes Tolo, was in Botswana at the time. He was part of the MK deployment in a structure called politico military council, serving as the secretary and political commissar.

The structure, copied by the ANC leadership of Oliver Tambo from the Vietnamese model, was formed after the ANC took a decision to combine the military wing and the political structure to further push the liberation struggle.

“We were jubilant about the release but we immediately knew that our strategy to bring down the apartheid government and democratise South Africa was not achieved. We also knew that the regime could no longer govern the country in the old way it used to. We also knew that the strategy of isolating apartheid internationally was gaining momentum. And, lastly, we knew that we were all going home and we were breaking with the past exile,” Tolo explains.

He says the key expectation then was to deliver democracy where our people could for the first time elect a government of their own and “that objective has been met”. The second issue was the abolition of the Group Areas Act – which would allow our children to attend whatever school was available, without discrimination – and that has also been met.

But now we have a high level of unemployment that sees the economy in the hands of whites. “The land issue has not been addressed and our people, the majority of black South Africans, are still locked in the villages and in the townships, and do not have access to the land and therefore the means of production.

“There is a high level of crime, and we were dreaming of a South Africa where there would be peace and security. One thing that makes my heart bleed is the killing of children and women. It takes everything away and it moves contrary to the South Africa that we had envisioned.” Tolo says the education system is not empowering young people to participate in building the economy of this country and creating out of them the owners and emerging captains of industry.

“I’m also not sure that our system has managed to eradicate illiteracy totally.” He says certain objectives have been achieved but many are still outstanding. “We should make sure that we reconnect those successes of the struggle and the victories that we scored, so that we start to build the South Africa of our dreams.”

Ronnie Kasrils

I was underground in Botswana on a mission and it was incredibly exciting and almost unbelievable. I couldn’t celebrate openly because of the underground situation, but I was overjoyed and it took me back to the period of the Rivonia arrests and the trial, when I was on the run in 1963.

I had known Sisulu best and had quite an interaction with him and the MK underground. You know he was such a lovable person and had met with Mandela and Thabo Mbeki. I knew Mlangeni very briefly. These people were like one’s older brother and you just had that absolute surge of enjoyment that at last they were released and one was beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel of all the gruesome years of apartheid. So it was a moment of incredible joy.

I soon met them in Lusaka when they arrived on their first trip, and I remember Harry Gwala was among them as well and it was wonderful celebrating with them when they arrived there in that open and public manner.

This question takes one back in time 31 years and it is so unbelievable that those years seem to have sped past like lightning. We think back and it’s tempered with the fact that most of them had long lives, which was very fortunate indeed. The whole history of the struggle against apartheid, this is like looking at the history book of my 82 years.

These Rivonia Trialists were the giants of us all. The younger generation today needs to just turn a corner and save South Africa so they can remain the incredible inspiration of their lives and sacrifice and, above all, they need to get the honesty and integrity of that generation and their devotion. They were very modest people.

Mavuso Msimango

When we heard the news, there was great rejoicing. I was in Addis Ababa at the time, in Ethiopia, with the UN. It was a day of rejoicing internationally, particularly when Mandela was released.

April 27 1994 must be the biggest day in every South African’s calendar; it marked the end of centuries of colonisation and decades of apartheid.

Everyone had the right to vote and they voted Mandela’s party into government. That was a strong statement mainly by the ordinary people. We couldn’t have asked for a greater endorsement of the ANC because of the role it had played. Although it wasn’t alone, it clearly played the leading role in the fight for freedom.

People were fighting to improve the lives of the ordinary people.

That could be measured in how many had no houses before and managed to get houses, including water for people in urban and rural areas brought closer to their houses. Sanitation was improved, with diseases brought by poor sanitation receding, and treatment in hospitals was available free of charge. Education became free. And some those changes were immediate.

The expectation, of course, was that we couldn’t solve all these problems in a short period of time and that the government would continue to provide municipal services and water, and also ensure that the land taken wrongly be returned to the people. We saw people whose land was taken after 1913 get laws that would allow them to get their land back.

Some, because of the process, didn’t; although these things were not happening perfectly, they were happening. The education system started with an experiment that went awry. Today we still lack strong education, especially in quality and demonstration.

When South Africa is compared with other countries, we are coming at the bottom, so something is not happening well with our education system, which has led to agitation about the cost of universities which led to the #FeesMustFall movement, demanding free education. What has really gone wrong in our country is the onset of corruption and its increase in the country and the ANC.

The party is so closely related with corruption that it is not easy to root out. It has lost a lot of the people’s confidence; you couldn’t have imagined the ANC losing in municipality power hubs like Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay.

These are the strongholds of the party, with the best people who fought for liberation; now it is lost mainly because people continue to lose confidence in the ANC because of the corruption. It has gone even worse today in the pandemic, where no one really knows how to handle it best.

This pandemic was managed much better than [previous ones], thanks to evolving medicine but when you’re having such an attack on the nation and the consequences of losses of jobs and lives, it’s scary. That there are people who are associated with the ANC stealing food from the poor or positioning themselves to get extortionist is indescribable. No one thought this would happen 26 years ago when freedom came in 1994.

Corruption is the dominant feature of the ANC. I don’t know, many jokes are made about the ANC and people are angry with the ANC. Rightly so. We really need to work hard; it is not easy and it’s not going to be easy to stop this corruption. What makes it difficult is that it has gone right to the top.

When the national executive committee said it wanted a list of corrupt individuals, it was a good thing because, for the first time, they acted, but it’s more than a month and we have no idea how it is going; where are the ethics and morals?

There is no serious ANC person who believes in the values of the ANC who thinks they can continue plundering and nothing can be done to them. This is a problem that needs to be fought.

Reverend Frank Chikane

The decision to begin to release the Rivonia trialists was an indicator to us that the struggle we waged was bearing fruit. The demand was very clear that the prisoners must be released because we could not negotiate while they were in prison.

It was in the heat of the United Democratic Front campaign, but, remember, I was general secretary of the SA Council of Churches (SACC).

By February 1988 all the liberation organisations were restricted, that is why the church leaders went to march at Parliament. Between 1988 and 1989 it was tough in this country; as you would know, Khotso House, the council headquarters, was blown up and I was poisoned. The SACC become the only voice.

They could not do much in prison so we had to make sure that they got out of prison.

When Walter Sisulu was released we worked with him and he was helpful in advising us how to handle the Mandela release, which we did. The only anxiety was about their security when they are released; that was a real concern.

My views are very clear. In 2015 I did my journey from home to Luthuli House because it was clear that we were diverting from the trajectory that we had set for ourselves. Then people began to be corrupt and self-serving and to looting the coffers of the state, capturing the state.

It started with the intelligence services, police and prosecution authorities. That is not what we struggled for or what Mandela and others were in prison for. I made a submission of 33 pages; we made it public and I presented the document to the top six to say we were deviating from what our predecessors wanted. I have wounds myself because I was in detention many times and got tortured many times.

We cannot sit here and allow the state to be captured, and individuals and families to benefit from the money of the people.

Even now we are working with the churches and we are saying we cannot allow the corrupt who stole money from the people while so many remain hungry and live in townships with sewage running in the streets and places where there is no water.

It is impermissible when people take billions of rands and put it into their pockets. We have said very clearly, they must go to jail.